Learning from science for better decisions and policies

The secret is focusing on how science works, not what it produces.

The scientific method has, over time, proven to be an effective approach for testing ideas and improving our understanding of the world. The rhetoric we often hear about science is its success is because it deals with data, facts and observations. However, we often hear less about the foundational role of theory in scientific practice despite its historical importance. A good demonstration is that much of the revolutionary science that has shaped how we think today is always talked about in terms of a series of theories: the theory of general relativity, germ theory of disease, the theory of evolution and so on.

This reliance on theories, rather than just facts and observations, is not a historical quirk or a weakness but captures the way in which science reflects basic structures of human knowledge. We rarely know the world directly but instead form abstract representations - theories, concepts, pictures, principles - that describe the world for us and which we can test for accuracy. This might sound highly abstract but turns out to be highly practical and efficient.

For example, if I am interested in building a new house, I am confident I can trust architects and builders to advise me on what will work and what won't work as a design. This isn't because they have already built every possible design and so know from experience what works, but they have a range of useful theories that help them figure out how things will work in practice. Some of these theories are simple principles and some are highly technical and computational, but they all capture what we know about how the world works in a simplified and comprehensible form. They both allow us to make informed plans before we build but also, when something goes wrong, show us where to look so we can improve next time.

Theory in Science

The constant interplay between theory - what we expect to happen in the world - and practice - what actually happens - is the core engine of the scientific method. Anyone who studied science at high school or university may remember how this is encoded in the standard formula for a scientific report. It starts with an Aim that articulates what we want to achieve, understand or test with an experiment. Next, comes the Background that covers the reasons why the experiment is important and the theories that underpin the experimental approach and goals. Then comes the Method, which describes the plan and how the experiment was done in practice and the Results that set out what was discovered in the experiment. The Discussion is a critical examination of the whole experiment, reflecting on how well the Method worked and comparing the Results to what was expected.

My memories of this are that writing the Background generally felt rather pointless for the experiments we did. However, with hindsight, I've realised that it is the critical piece that connects the Aim and the Method. If we have not articulated how we expect things to work in the world, that is, if we haven't articulated the background theory, there is no way we can know if the described method can actually support or deliver the Aim.1

When the experiment does not work out like we expect, the background theory is a critical component of the Discussion as it helps identify what went wrong and why. Without understanding our expectations about how the world works, it is very difficult to meaningfully diagnose whether the issues were in the experimental methods, design, or overall structure.

When perfectly executed plans fail

In my experience, when some policy or plan fails, our instincts are to go back and look at why the implementation didn't work - perhaps we got the costs or timelines wrong, or there was some external factor that threw our plans out. However, it is also common for policies to fail because the plan or implementation is insufficient to deliver on the intended goal or outcome. That is, we can deliver the implementation plan perfectly and fail to achieve the desired outcome. For example, in government, economic measures sometimes fail to improve the economy and support for vulnerable people sometimes doesn't make them less vulnerable.

A couple of examples might help illustrate this. To start with, the US-led intervention in Iraq is widely considered a failure. This is despite the fact that the intended method (military intervention to remove Saddam Hussein) for achieving the stated goal (of establishing a modern democratic state in Iraq) was easily delivered. The problem was that the method wasn't sufficient for delivering the outcome and very little thought or planning seems to have gone into filling this gap.

Or to pick a very current example from the last week, Apple released an ad for its latest iPad Pro that backfired and Apple apologised after a couple of days. For those who haven't seen it, it picks up on an online trend and shows a giant plate crushing a whole range of objects like musical instruments, books and paint - with the result being the new iPad Pro. It is a compelling piece of cinematography and yet had the opposite effect to what was intended.

In examples like this, the structure of a scientific experiment can help explain what happened. Each is like a scientific experiment where we followed the Method exactly and yet we failed to achieve the Aim. As noted above, this means that there is a clear gap or flaw in the Background or Theory. Our understanding of the world around the experiment was insufficient so that when we followed the Method it didn't have the effects that we would have expected. Either it means our background and theory were wrong, or there were big gaps in them.

I expect that, in both of these cases, the problem was more a gap - there was a lack of articulated expectations and theory. From what we have learnt, there doesn't seem to have been a detailed explanation of how existing Iraqi society and culture would smoothly shift to a modern democracy following the removal of Saddam Hussein. Or, if there was one, it was clearly flawed. Likewise, it seems unlikely that Apple had a clearly articulated theory about how showing lots of things that people value getting destroyed would lead to a positive impression of the new iPad.

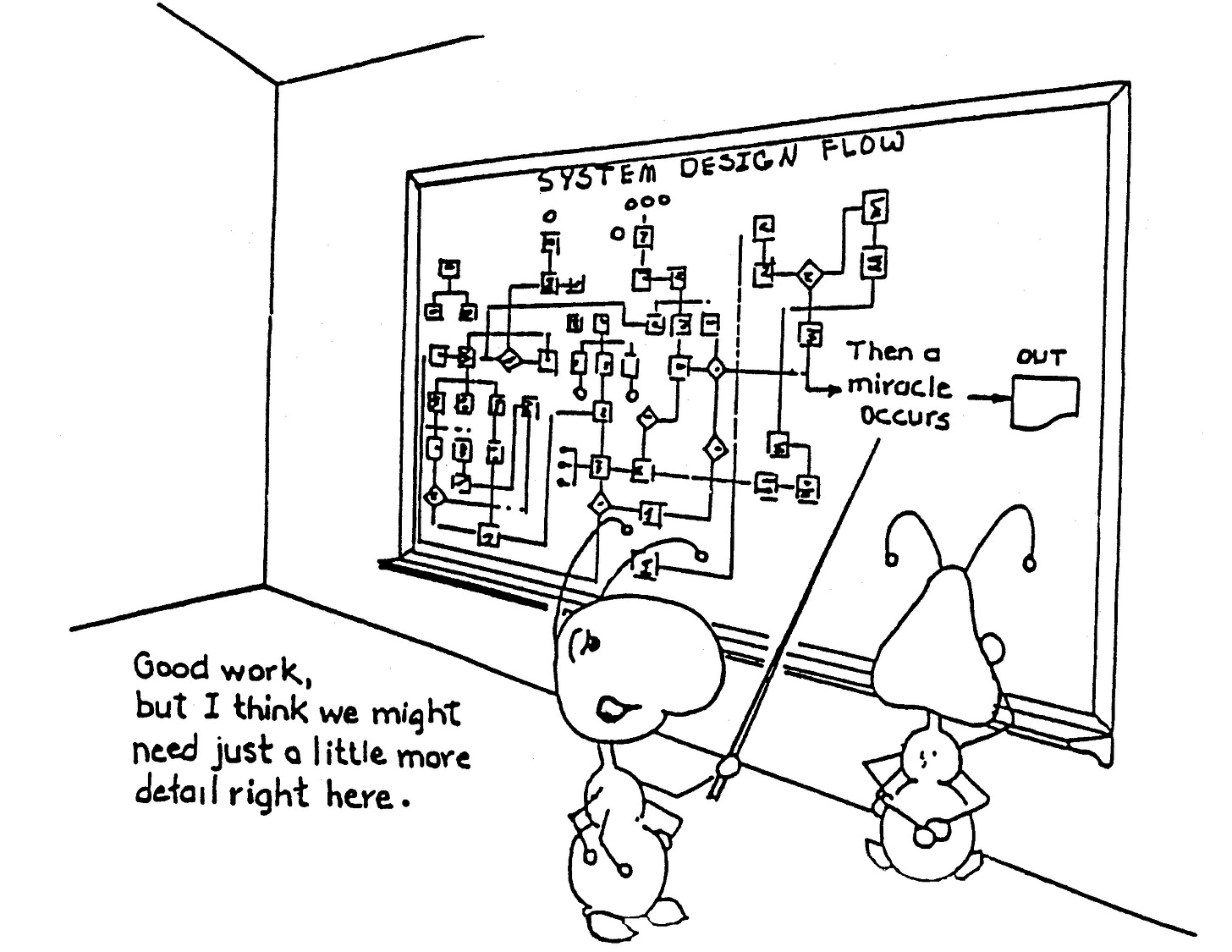

Both, like many decisions, seem to have relied on feelings or vibes about what would happen and ended up with a plan that looks a lot like this:

Making theory explicit in decision making

Things don't work and poor decisions are made for a wide range of reasons, some of which are unavoidable. But a common avoidable reason is that we have not clearly articulated our background theory and expectations that explain why the plan we are adopting will lead to the desired outcome. For example, how will businesses act when a government changes the tax rules? What will consumers do when a business changes the product it is selling? How will disadvantaged people respond to a change in the structure of welfare payments? When and why do people follow legislation and when do they ignore it?

Many of us have a gut feel sense of the answers to questions like these but, in my experience, it is rare to see these expectations and background theoretical assumptions set out clearly in the development of policies and plans. We assume, or in some cases hope, that the actions will deliver the desired outcome.

Making this background theory clear is an important step that can help avoid flawed decisions and need not require a huge investment of time or resources. While ideally we might want a fully developed scientific theory built on deep research, randomised control trials, or similar approaches, articulating the background theory is a simple and often powerful starting point. That is, we should clearly articulate how and why we think the plan or policies will, in the real world, deliver the desired outcomes.

Clearly articulating these expectations - the background theory - will help improve the rigour of our analysis and lead to more robust decisions in a few ways. The first is that making it explicit often ensures flaws in our logic or plans are easier to see. For example, governments regularly want to bring in new legislation or regulations under the expectation or assumption that this will lead to a change in behaviour, but simply changing the rules without any sort of enforcement rarely makes a lasting difference. So a plan for new rules without any plan for compliance or enforcement is likely to be ineffective.

A second advantage is that explicitly stating the background theory makes it easier for others with different perspectives or insights to challenge our thinking and point out dynamics that we hadn't thought about. Instead of arguing over the policy or plan, it is often more constructive to understand differences in background expectations about how the world works and then understand how they will affect the plan. This can also make points of disagreement clearer by identifying where exactly the differences lie.

A third reason is that it makes evaluation easier and more useful. Our analogy of a scientific experiment is again useful here. In a well conducted experiment, we have articulated a clear Method that is designed to deliver or test some Aim and then we measure Results to confirm whether it does. Underpinning all of this is the Background and Theory that explains how the Method connects to and delivers the Aim.

After the experiment we can then seriously reflect on all the features of this. Did the Results support the Aim? Was there some flaw in the Method that didn't work? Or was the Method disconnected from the Aim as our Background was missing something? Or was the Aim misplaced? The clear articulation of all parts of the experiment allow us to genuinely evaluate the experiment and identify more precisely where things went wrong, if they did.

However, too often, policies and programs only articulate the plan. This means we can only evaluate whether the plan was delivered as expected. But without a clear understanding of the objectives and the background theory and expectations, it is hard to evaluate whether the policy or program was fit for purpose and whether it is delivering the real world change we wanted.

A clear statement of our expectations of how a policy or program will function in the real world then gives a useful framework for evaluation. We can watch and see where practice deviated from our expectations (or theory) and more easily identify potential improvements.

Make policy more scientific

We often hear calls for government and business decision making to become more scientific. Most often this is a call for decision-making to use data more heavily, or rely on the advice of scientists, or adopt explicit experimental methods like randomised control trials.

While there is an argument for all of these in different circumstances, they miss the underlying strength and advantage of scientific methods. These build on the interplay between our expectations of how the world works (theory) and what happens in practice (experiment). Making both of these explicit in decision making will make it more scientific in a simple but meaningful way and will help the quality of our decisions.

For those who are interested, Pierre Duhem is well-known in the Philosophy of Science for demonstrating how theory dependent even basic measurements in science often are.

Excellent. Is there a better word than background? Underpinning perhaps? Do we need a phrase that takes it from the realm of simple (boring) description to something essential that deserves to be thought about.