Sometimes rationality leads us astray

We need to pay more attention to when and why we are being rational

When someone makes a poor decision, or end ups with crazy convictions, we often express the wish that they would be more rational. More generally, we typically assume that, if people would take time to think things through rationally, many problems in our world would disappear. The reason this doesn’t happen is often expressed as the conviction that humans are only rarely rational, with cognitive biases being common evidence for our limitations. Many have high hopes for AI for precisely this reason - AI is presumed to be rational where humans aren’t.

However, this whole discussion is muddied by the way it assumes rationality to be a skill or practice that is clear and well defined. When we look more closely, we find that ‘rationality’ often means different things in different contexts. Moreover, in at least some cases, being highly rational causes more problems than it solves.

One useful, but not complete, way of seeing this is to track through the process that we, as humans, use to build knowledge and which I've been exploring over the past few months. What follows uses this framework to sketch out some incomplete ideas about rationality.

Tracking the structure of knowledge

As a reminder, I've argued that human knowledge emerges from a dynamic process that moves between different thinking systems. This starts with (i) some kind of observation or experience of the world, which then (ii) prompts us to come up with a theory or hypothesis about how the world works. We then (iii) flesh out this theory or hypothesis to think about what it would mean and what the consequences are. The next stage is (or should be) (iv) testing these consequences against the world, either via existing evidence or hunting something new out. If the consequences turn out to not match the real world then (v) we revisit or abandon our theory or hypothesis.

This process that moves from looking at the world, to formulating or constructing a theory, and then back to the world is characterised by the neuroscientist Iain McGilchrist as moving from the right hemisphere of the brain to the left hempisphere and back to the right again.

Interestingly, what we count as rational behaviour varies at the different stages of this process. For ease of explanation, we will go through them in reverse order.

At stage (v), when faced with a match, or mismatch, between our theories (or how we think the world works) and what is actually happening, it is fairly clear that the rational action to take is to take this information into account and improve our theories where needed. That said, we tend to be careful about when we change our minds as we typically do not have the capacity or energy to do this every time it might be relevant. But it is clearly irrational to face a major and genuine issue with how we think the world works and not do anything about it.

In stage (iv), what counts as rational behaviour is also clear. We should genuinely test the consequences we have identified from our theories against the full range of (reliable) evidence that we can find. We would also expect to weigh different types of evidence to see where the weight of evidence might lie. To ignore relevant evidence or not test what we think where there is an opportunity to do so, is not rational behaviour if we care about knowledge.

Practical human behaviour is often not fully rational on these terms. There are often good reasons, perhaps reducing effort or for social reasons, to not bother with all the evidence. The most common cognitive bias, confirmation bias, is a clear example of failing to be rational at this point.

Rationality is a very different type of skill in stage (iii). It is not about the type of decision we should make (as in v) or how we should look around us in the world (as in iv) but is more about how our theories fit together and what their consequences are. Fleshing out a theory or hypothesis rationally requires thinking through what would follow if the theory is true and working through a range of consequences on related theories, phenomena or dynamics. Being rational here involves not making large leaps of logic or just putting similar feeling concepts together. It is the rationality of the mathematician or the deductive logician.

When we look at stage (ii), it is easier to identify what counts as clearly irrational. To start with, it is obviously irrational to come up with a theory or hypothesis that doesn't actually explain the observation or experience we are trying to understand. This does happen though, particularly when people often see everything as evidence of their own pet theory. A second clearly irrational approach is to come up with a theory that is completely at odds with everything else we know. We often see this expressed when people respond to an idea by saying something like: “that's crazy, because it would mean X or Y and they definitely aren't true”.

It might not look like rationality comes into play during stage (i) when we are focused on observation and experience, but we often enforce standards of rationality when doing so. It is common to decide that something we see or hear as not real because it doesn't fit what we understand is possible. Perhaps that thing you saw wasn’t a ghost as we know they don't exist. At extremes, it is possible for people to literally not see or hear something because they don't think it is possible.

Importantly, what we consider to be possible is entirely a function of the theories, stories or worldview we have accepted as true and count as knowledge. What we count as rational behaviour during stage (i) involves, like in stage (ii), checking against what we already know.

When is rational reasoning helpful?

This is not an exhaustive analysis of the different types of skills or behaviours that we count as rational, but already we have identified five different types. It includes:

choosing to change our mind when the evidence says so;

genuinely testing ideas or theories against sufficient evidence;

working through our thinking with rigour and logic;

ensuring our ideas or theories actually match (or make sense of) the part of the world that is relevant; and

ensuring anything new fits clearly with what we already know.

The challenge then, if we are asking people to be more rational, is to be clear about which of these we are referring to in any particular context. We might be talking about all of them, but applying the right one in the right context matters. It isn’t uncommon for some of these rational processes to lead us in the wrong direction. Let’s look at two illustrative examples.

The rational approach to counting observations and building new theories is to ensure it is coherent with what we already know. Otherwise we are likely to end up trying to completely rebuild everything we know from scratch all the time. However, this highly rational approach is also responsible for delaying, or preventing, the acceptance of new scientific theories. Just about every major scientific breakthrough involves reconceptualising, or throwing out, existing knowledge. The resistance to Ignaz Semmelweis' discoveries about the importance of hospital hygeine that I have written about a couple of times before is a good example. The rational approach of ensuring new ideas fit with existing knowledge can work against accepting valuable new ideas and new knowledge.

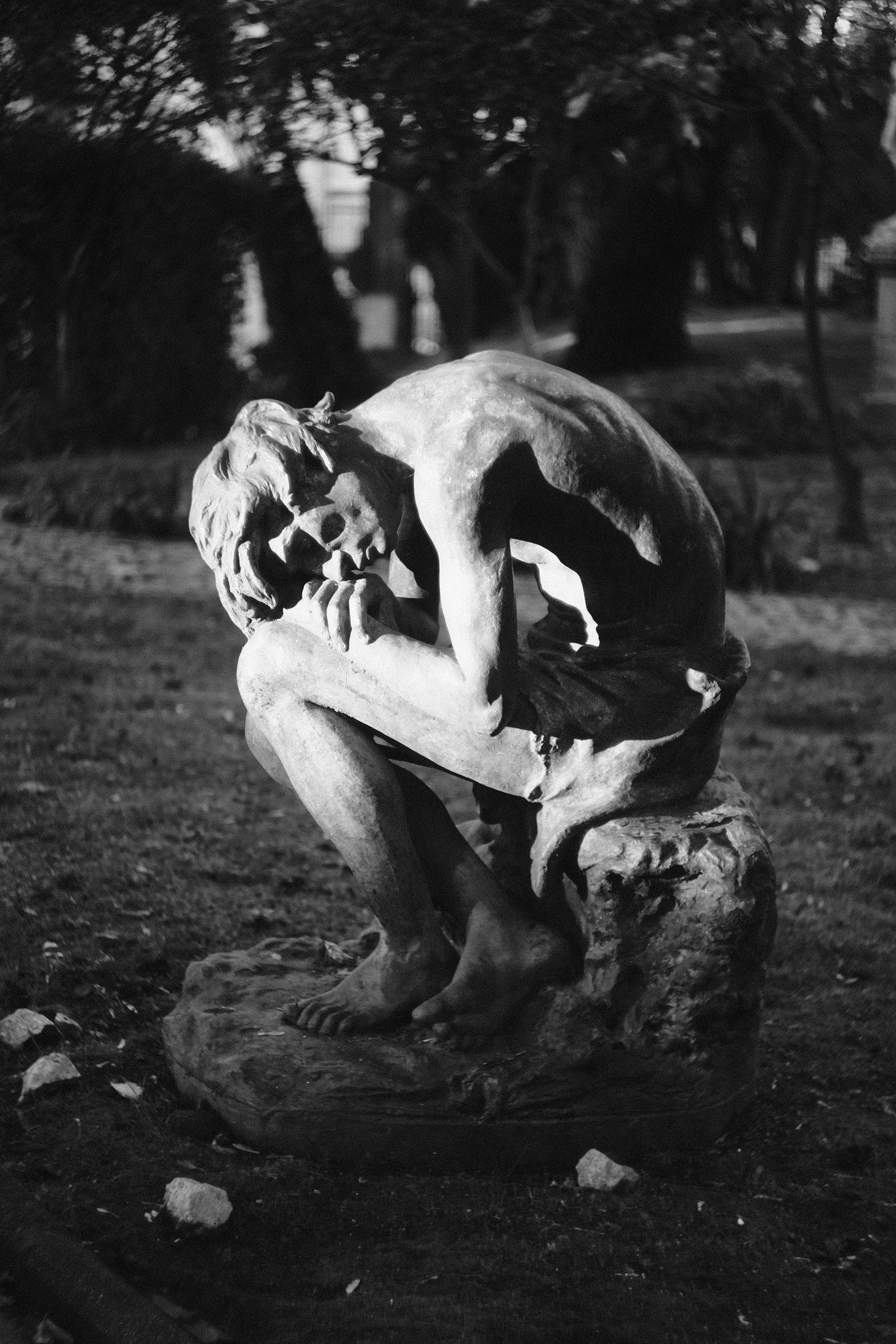

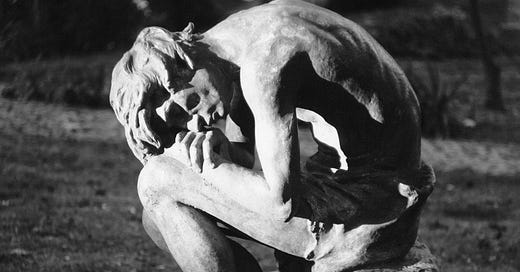

A second example involves the rigour and logic that goes into theory-building. Consider people who have genuine paranoia and are convinced there is some kind of conspiracy of people out to monitor them. When you interact with them it becomes fairly clear that, while what they are saying often sounds crazy, it is almost always put together with incredibly detailed and precise logic. Everything fits neatly and is beautifully explained by the hypothesis that they are being monitored. It also often adds a meaningful narrative consistency to every day life as things no longer happen randomly but there is a clear reason behind otherwise meaningless events.

In terms of the coherent, logical theory building aspect to rationality, people like this are often hyper-rational. Their core assumptions and theory may be completely untrue, but everything fits together very coherently. Asking someone like this to be more rational, if we aren’t clear about what aspect of being rational we mean, can make the problem worse.

When should we be more rational?

So just expecting people to be more rational isn’t helpful if we aren’t clear about what particular skills or aspect of rationality we mean. This is especially the case as, sometimes, these lead us away from better knowledge or practice. So what can we say about when and how we should be rational?

My starting point is my repeated argument that we need to be humble about what we know and accept we will often get things wrong. It is always important to check our knowledge against the only external standard we have - reality - and take that as driving our decisions, not just what we think we know.

This means that, if we look at the five stages in the human thinking process set out above, it is most important to be careful and rational in the latter two stages - (iv) testing and (v) updating our theories.

By contrast, being highly rational at the front end and strictly policing new ideas based on whether they fit our existing theories, is not consistent with a humble approach to knowledge. It assumes that we can be highly confident, perhaps even certain, about what we already know and can use that as a reliable test of truth. Being humble means we need to test a range of ideas or theories we expect to be wrong. It is less important to be rational in the (i) observations and (ii) idea/theory generation stages - so long as we rigorously test whether they match reality at the end.

Unfortunately, in my view, allowing crazier ideas when we are coming up with what we think and then being far more careful and rational when we test what we think about reality is the opposite of what many of us do. Instead, we carefully police new ideas as to whether they fit with what we already think and, once we have a theory we are happy with, avoid changing our minds unless the evidence is overwhelming.

This is excellent but.......I wonder

Is it possible that this reflects a little confirmation bias? Intuitively, allowing more random thinking at the beginning of the process makes sense. But a question arises about how you define 'crazy' in a way that limits the field of possibilities from which theories are formed and tested. Also how well does this address the problems of rationality you identify.

As an aside, the process you outline lends itself (I think) to more group based thinking at the beginning of the process to ensure you trap enough diversity and step outside the constraints of rationality.