What is true versus what works

On Pragmatism and the logical structure of truth

In my recent writing on knowledge - and the reasons why we don't change our minds easily - I have been deliberately taking a pragmatic approach. My focus was on the practical role that knowledge plays in our (individual) lives and the consequences of this. I put to one side any questions about whether our knowledge is actually true so as not to confuse an analysis of how knowledge actually operates for us with any questions about how knowledge should work. This approach, I have realised, has strong echoes of a distinctively American tradition of philosophy that sought to avoid metaphysical considerations like truth in favour of focusing on what works: pragmatism.

Pragmatism, as a philosophical tradition, is commonly associated with CS Peirce, William James and Richard Rorty. We have met one of Peirce’s core ideas previously. He coined the idea of abduction as a distinct method of reasoning separate from induction and deduction. He took his inspiration for this, and pragmatism more generally, from scientific practice. In science, what matters most is whether scientific theories make accurate predictions. In other words our criteria for whether theories are true is to ask whether they work in practice.

Richard Rorty took this idea further with the observation that language, and all assertions of truth, are human constructed and mind dependent. Rorty argued that it was not possible, but also not necessary, to transcend this mind dependent realm to meaningfully talk about and decide on truth. Like Peirce, what mattered was whether statements and language worked, whether they could be successfully put into practice to achieve our ends.

There are good intuitions behind this approach. My statement that the door is unlocked is only true, for any reasons that generally matter, if it means anyone can open the door without a key. That is, the statement is true whenever it works pragmatically.

A false equivalence

While I agree that whether a statement or belief 'works' is a critical consideration as to whether it is true, I’d argue the broader pragmatist approach is built on a logical conflation.

In logic, there is an important difference between an inference (or an "If ... Then ...." relationship) and an equivalence (or an "If and only if" relationship). For example, "If it is raining outside then my lawn gets watered" is an inference - one thing happens when the other does, but not vice versa. An equivalence, on the other hand, goes both ways. In this case it would be that "Every time it rains my lawn gets watered and my lawn only gets watered when it rains." It may be true if I don't use a sprinkler or hose, but here in Australia that will quickly lead to a dead lawn.

If we follow Peirce and focus on scientific practice as our case study, we can see that the relationship between truth and ‘what works’ is an inference, not an equivalence. If a theory is true, then it will work; but theories that work aren't necessarily true.

To see the inference, we just need to focus on the core scientific method. You start by formulating a theory, use that to make hypotheses about what will happen in the real world, and then test these via experiment or data. This whole method assumes that if a theory is true then it will work as a prediction of how the world will work. The inference that “If it is true, then it will work” is foundational for scientific practice.

By contrast, just because something works as a prediction, it doesn't mean that scientists take it as true. By way of example, let's go back in history to look at the famous 'Copernican Revolution' - the shift from believing the Sun (and other objects in the sky) revolve around the Earth to accepting the Earth revolves around the Sun.

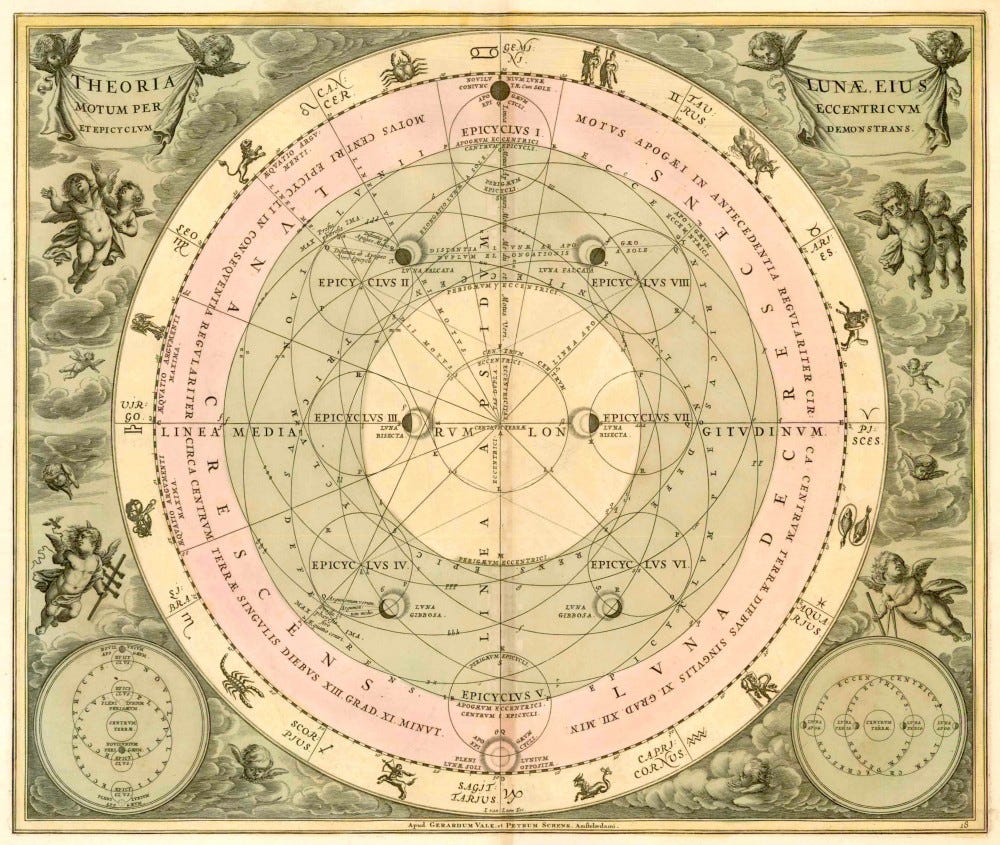

From Ancient Greek and Roman times, through the Medieval period, scientists and philosophers believed (i) that the Sun, planets and stars revolved around the Earth and (ii) Celestial objects moved in perfect circles as they weren't corrupted like things were here on Earth. This sounds weird to us, but it worked very well to describe and predict the motion of entities in what we now call Space. The important insight was to allow for both large circular orbits and smaller circles (called epicycles) around the orbit. Scientists derived highly sophisticated models that looked like this:

These models of movement worked very well in precisely the sense that Peirce cared about. They worked for making predictions, and initially worked better than anything Copernicus or the others who argued the Earth revolved around the Sun came up with. Therefore, according to the pragmatists, the fact they worked should have been enough to consider that they were true. However, scientists at the time didn't accept this and, over time, we ended up with a much more sophisticated in depth understanding of the universe. The fact that a theory works in real ways doesn't mean it is true.

Another way of seeing this is to use what logicians call the contrapositive. That is, for a statement of form "If P then Q", its contrapositive is the statement that "If not-Q then not-P". The important logical point is that statements and their contrapositives are always true and false together (which makes sense if you think it through). So in this case, "If a theory is not true then it won't work" (the contrapositive) is equivalent to "If a theory works then it is true". Let's consider a ridiculous example to show how this contrapositive isn’t always true.

Perhaps I have been working hard and have come up with a new theory to explain the way that electricity works. While physicists think about electrons and charge and current, I have decided that they have a much too narrow and sterile view of the world. What they haven't realised is that there are magical metal fairies that live in all kinds of pure metal and what these fairies love to do more than anything else is to have a big party. When they party, they give off a huge amount of energy that we harness in things like light globes and appliances. However, they can only party when they get the right sort of music going - and generators and batteries are really a source of music that flows down the wires. Switches determine whether the music can flow, voltage is a measure of how loud the music will be, current is a measure of how big the party is and AC vs DC are different sorts of music.

This clearly isn't true, but it works very nicely to explain lots of facts about electricity. For example, some metal wires aren't strong enough to hold a really big party, and so when the party gets too big, they melt down and the party stops. (Likely as metal fairies aren't known for their self-control.)

Here we have a theory that isn’t true, but does work as a prediction or explanation of many things. And there is nothing special about this example - we can come up with lots of similar cases. In all these cases, we can conclude that a theory working doesn’t mean that it is true.

‘It is true’ implies ‘it works’

In summary, a theory that is true will necessarily work as an explanation or prediction of the world. But the opposite doesn’t always hold: theories that work aren't necessarily true. This particular logical relationship - a kind of syllogism - explains some notable features of the way truth and knowledge work.

For example, it neatly explains a feature of scientific practice identified by Karl Popper. He argued that it is not possible to decisively prove that a theory is true, whereas it is possible to decisively prove a theory is false. For Popper, science progressed on the basis of ‘falsifying’ theories, or proving theories wrong. This insight follows directly from the logic we have identified.

The contrapositive of our conclusion that "If a theory is true, then it will work" is that "If a theory doesn't work, then it isn't true." All our scientific experiments are in the realm of figuring out whether something works. Experiments sometimes clearly show that a theory doesn’t work, and it therefore follows that the theory is not true. In Popper’s words, we can falsify it. However, as we have seen above, the fact that an experiment confirms a theory - shows that it works - does not prove that it is true. Theories that work aren’t always true.

This illuminates a frustrating asymmetry at the heart of truth and knowledge. In a strict logical sense, we can prove that a theory isn’t true, but we cannot prove any theory is true. We can only get to truth indirectly, by observing effects and judging whether our theory is the best explanation or finding out whether it can be disproven. The fact a theory works in a given situation gives us useful information, but it isn't decisive as to whether it is true.

This asymmetry gives us another reason to be humble about what we know. It is much easier to rule theories out as false than to prove that what we think is true, and so there is always the real chance that what we think we know turns out to be wrong.

Denying this asymmetry, on the other hand, can license all sorts of poor epistemic behaviour. I’ll highlight one that frames a particularly poignant criticism of Pragmatism, and Richard Rorty in particular. He is now well known for his prediction, before his death in 2007, of the rise of a populist figure like Donald Trump.

However, it has been noted that the attitude at the heart of pragmatism, that whatever works is what is true, neatly describes Trump's (and many other politicians' and salespeople's) attitude towards truth. For these people, whatever works in terms of achieving my goals or ends is what is true, and therefore they can (in their mind) truthfully assert anything they think will work. As almost no-one would agree that Trump, or similar salespeople, are truthful, this is a clear sign that something is wrong with the pragmatist approach to truth.

Excellent. True or not, I am for the metal fairies.